[ad_1]

Maria* vividly remembers the fateful day of the attempted assassination. The sound of gunshots ricocheting from an assailant’s weapon into her parked vehicle and striking her body is a continuous nightmare that recurs in her mind.

Maria, a prominent activist for the rights of Indigenous Filipinos, received gunshot wounds to her left underarm that were inflicted by armed assailants seeking ownership of her community’s ancestral territory. The result was lung damage, multiple rib fractures, 17 stitches from underarm surgery, and three stitches on her back where the 45-caliber bullet was extracted.

Following the incident, Maria filed her case with a local police station in Bukidnon province, located in the northern Mindanao region of the southern Philippines. Yet, there have been no warrants issued to identify the suspect.

“The criminals are freely given the chance to roam throughout the ancestral domain and are waiting for their next victim,” Maria said in a phone conversation.

Maria, a mother in her sixties, is a member of the Matigsalug tribe. Advancing the welfare of the Matigsalug has been a continuous battle that began with her family members who partnered with government officials seeking welfare reform for Indigenous populations on the national level. Today, Maria continues her family’s advocacy as an active adviser in her community for her fellow tribespeople—often encouraging their narratives to be recorded as affidavits.

‘An extension of our life’

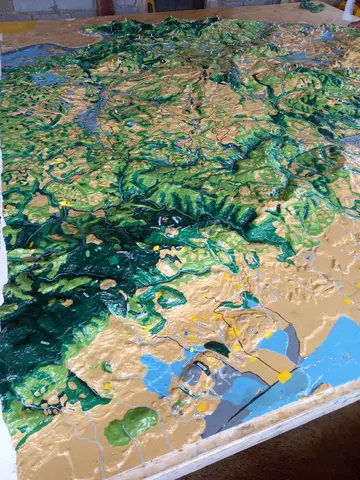

Mindanao’s plethora of rich resources on Indigenous land, including timber, gold, and nickel, have attracted the interests of investors from logging, energy, and mining corporations throughout Asia. Commercial logging grew in the late 1950s with Mindanao as one of the top suppliers of lumber, plywood, and veneer in the nation. According to the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (UNHCR), large portions of the Matigsalug’s ancestral domain were occupied by private logging corporations from 1960 to 1975.

Dr. Irina Wenk of the University of Zurich reports around 164 logging concessionaires with 25-year leases held a total concession area of 5,029,340 hectares (12,427,770 acres) in 1979. However, the total commercial forest land area of Mindanao encompasses 3,920,000 hectares (9,686,530 acres), making the concession areas much higher than projected.

By the 1990s, only a fifth of the region’s forests remained. Sixteen percent of the land remained forested or regrew as secondary forest in Matigsalug territory. With the landscape transformed into grassland, traditional farmers struggled to generate productivity and adapt to a new agricultural lifestyle.

Nature is heavily ingrained in the community’s heritage. Celebrations of good harvest, known as Simud for Panubad, featuring traditional songs, dances, rituals, and offerings to spirits continue with each generation. Spirits hold a deep-rooted connection to the land. Local spirits are considered the primary owners of properties and are consulted prior to any human activities being conducted on tribal land.

Collectively, the tribe shares ownership of the land. Maria says, “Families become dislocated once properties are sold. And those that decline offers are subjected to harassment. We cannot trust anyone.”

Maria recounts a tragedy involving a couple who were close allies and had had provided free legal services to the tribal community—both were shot and killed by an unknown assailant. One of the couple was a prominent lawyer vocal in providing justice for tribesmen.

“The two were always willing to help anyone in need,” Maria says. “This tragedy should be taken seriously and be given justice. This case is just one of the many left without action.”

Land grabs occur in neighboring provinces. Timuay Cio of the Lambangian tribe resides about 227 kilometers (141 miles) from Bukidnon in Maguindanao province. He serves as a tribal leader and oversees the governance and justice system of the community in South Upi.

“We have encountered around 23 documented deaths in our territory over the protection of ancestral domain,” Cio writes in an email. “Many tribal members were forced to evacuate due to constant harassment by armed groups.”

Cio emphasizes his community has experienced rampant land grabs from mining operations on the ancestral domain by non-Indigenous persons.

The sale of Indigenous land is a dangerous business. Corporations seeking shares of the Matigsalug’s ancestral domain claim development will ensure mutual benefits for locals and investors alike. Some local leaders may be swayed to sell their ancestral domain due to investors promoting new job opportunities, increased tourism, and agricultural development generating profit. Yet, these projects often lack consideration of the tribal members’ needs nor do they include the voices of the tribal members in discussions.

Cio says, “Collaboration between corporations and influential politicians allows for false land titles to be sold and act as illegitimate legal documents. Corporations do not usually consider our tribe’s needs and lack free prior informed consent. Indigenous peoples have become landless and beggars on their own territory.”

Signe Leth serves as a senior adviser with the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) specializing in the rights of Indigenous women and land throughout Asia for over six years.

Leth says in an email, “Corporations and businesses are very often part of conflicts over Indigenous peoples’ ancestral domains. A number of powerful forces, including expensive multi-year mega development projects, extractive industries including mining, agribusiness, and energy projects, influence this conflict. Indigenous peoples in all regions of the world have paid and are still paying a high price for recent decades of unsustainable development. The global rush for economic growth has led to an increased demand for natural resources with Indigenous peoples’ land being a primary target for illicit acquisitions. Companies can both be national and international, including backing from international investors.”

Consequently, the traditions and access to resources for Indigenous communities are stripped away with the sale of land. “Our ancestral domain is an extension of our life,” Cio says. “The land is our source of food, medicine, and materials to build our homes. We have a very close relationship with the land in conducting our rituals. It is important for us to protect our land and its environment.”

“The land of Indigenous peoples is not just a commodity,” Leth says. “They have a deep connection to the land in their everyday life, cultural and spiritual practices, language, and healthcare systems. The land is their livelihood and home.”

She continues, “If their land is taken away, so is the identity, self-worth, and history. They gradually lose their language and assimilate into mainstream lifestyles, which depletes the world of diversity. So much knowledge is lost that has grown through each generation on how to take care of that particular land and utilize its resources sustainably.”

‘A clear unequal power balance’

Attempts to legally protect ancestral domains have been enacted by the Philippine government. In 1997, the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) was legislated, and the ancestral domain of Philippine tribes was recognized by the government. According to Chapter 3, Section 5 of the document, “The indigenous concept of ownership generally holds that ancestral domains are the ICC’s/IP’s (Indigenous Cultural Communities/Indigenous Peoples) private but community property which belongs to all generations and therefore cannot be sold, disposed or destroyed.”

Dr. Augusto Gatmaytan is a professor and researcher specializing in anthropology at the Ateneo de Davao University, where he has worked for more than 10 years. He co-founded the Legal Rights and Natural Resources Center to provide legal services, policy research, and advocacy to support Indigenous Filipinos.

He says in an email, “The Matigsalug, through their organization, the Federation of Matigsalug-Manobo Tribal Councils, Inc. (FEMMATRICS), received their Certificate of Ancestral Domains Title (CADT) No. R10-KIT-0703-001 on July 25, 2003 from the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP), in accordance with the provisions of the IPRA. The CADT covers some 102,000 hectares (252,047 acres) of land, one of the largest titled ancestral territories in Mindanao. Legally, this means the estimated 70,000 Matigsalug members of FEMMATRICS communally share this territory.”

“As outlined by the IPRA, none of the lands covered by the Matigsalugs’ CADT can legally be sold,” Gatmaytan continues. “However, despite these provisions, there are cases of sales of land by Matigsalug individuals or families to outsiders. Such virtual alienation of Indigenous land occurs due to insufficient enforcement of the IPRA, ambiguities regarding the legal status of ancestral land, economic enticement by outsiders, and the institutional inability of FEMMATRICS, a relatively new, inter-community institution, to regulate its members and transactions.”

Following the implementation of the IPRA, the Philippines maintains progressive laws preventing the sale of ancestral land. However, it is not infallible. Leth says, “The laws in place are not always properly implemented. Corruption and fraudulent activity are often cited in the legal processes. Perpetrators are able to evade legal repercussions due to Indigenous communities being unaware of their rights and not having proper legislation in place to support them. It takes a lot of financial and human capital to fight these battles, which these communities often do not have.”

She concludes, “There is a clear unequal power balance.”

Maria agrees: “This is a power struggle. These outsiders have money, resources, and the backing of government officials to go about their plans, which our people lack. We are ultimately disregarded by those with authority.”

Despite the IPRA’s prohibition of the sale of ancestral land, perpetrators are able to evade authority.

“Regretfully, the IPRA has not proven to be a reliable defense against loss of land or resources due to ambiguities regarding the legal status of ancestral land,” Gatmaytan says. “There is a long-standing local discourse of interested parties arguing that any sale represents the free and informed decision of self-determining agents seeking to sell their land should be respected. There is also a disparity between the notion of ancestral domains as property owned communally, as certified by a CADT, versus distribution of land among a village, family, or individual maintaining control.”

Disparity within governing systems is evident and stunts progress in aiding Indigenous victims’ cases. Maria says, “Our heritage is being sold to the rich who have no connection to the land except interest in exploiting it. If we go to the police station or the government, we are discriminated against. Even if a case is filed, money is the main issue.”

Necessary accountability

Attacks on Maria and her community have not halted her battle for justice. Maria has organized outreach and advocacy for Indigenous people throughout the Philippines. She has formed a cooperative for tribes nationwide by combining Indigenous People Mandatory Representatives (IPMRs), tribal leaders responsible for representing Indigenous populations, and government. The cooperative writes letters to local and national leaders, including filing presidential complaints in order to receive greater support and accountability from the government.

“In order to stop these attacks on our land and people, leaders from all sides must come together,” Maria says. “We are combining our forces alongside various sectors of government, including the legislative and defense secretaries, to form a cooperative encompassing all barangays (districts). Government leaders will only take action once we organize ourselves.”

Gatmaytan says, “There are leaders who are genuinely concerned for their Indigenous constituents and look out for them. On the other hand, there are other leaders who are more interested in securing opportunities for personal profit or power as opposed to the rights and interests of Indigenous communities.”

Gatmaytan adds: “As a political institution, the Philippine national government has a limited programmatic response to the continued loss of land among Indigenous peoples. At the level of local governments, their response depends on their concern for their Indigenous constituencies.”

While legislation aiding Indigenous Filipinos is fundamental to promoting rights, activists say greater involvement is necessary. Land loss generates consequences for Indigenous people struggling to maintain their traditional roots. As a result, accountability must stem from leaders to protect the human rights of tribal communities.

“The government should provide livelihood programs to improve the economic and social situation of Indigenous persons, such that the idea of parting with their lands as a necessary sacrifice in the pursuit of their family’s welfare is no longer a viable, or even thinkable, option,” Gatmaytan says. “The continuous disintegration of Matigsalug territory is driven by economic need. The willful participation of the Matigsalug in these transactions must be accorded due attention.”

Leth says, “The government is the duty bearer and, as such, responsible to protect its citizens. It should have accessible processes for protection, redressing, and remedying violations of Indigenous persons’ rights. This is, however, not the case. The government should make cases of exemplary punishment of those who violate the rights of Indigenous people, but they do not. Instead, they act with impunity.”

Gatmaytan provides solutions addressing the legal disparities at the local and national levels. “A thorough administrative reform of the NCIP, which unfortunately has a reputation in many circles as being saddled with ineffectual officials and staff, can improve the structure of those responsible for overseeing Indigenous rights. Those proven to have been involved in illicit transactions should be terminated and penalized,” he says.

“Furthermore, the legal ambiguities of the NCIP should be addressed including making the IPRA more relevant and responsive to the evolving interests of Indigenous groups, communities, families, and individuals,” he continues. It is not just the government that should be addressing the issue of progressive land loss. The Matigsalug themselves should be discussing what is happening with their territory and, if they find it necessary, they themselves should be formulating and implementing measures to address the situation.”

“This is a matter for the Matigsalug to decide as a self-determining Indigenous people,” says Gatmaytan.

Maria emphasizes the importance of placing power back into the Matigsalug’s hands. “Education should be prioritized for younger generations in order for youth to obtain knowledge of their Indigenous rights. Let the children be educated to aid the future of our tribe. I know there is still hope,” she says.

Prioritizing the preservation of Indigenous communities’ integrity is vital. “We are fighting for our rights to preserve our land and culture. Equality never existed with ancestral land and until now, it is deprived of everything,” Maria says. “Welfare is just on paper.”

Maria’s message to perpetrators remains clear, stating, “I was raised there. I am fighting alongside my family. Even if you buy it, it will never be yours. Ancestral land will always be the property of the tribe.”

“We will remain standing on our land,” she says.

*Editor’s Note: Not her real name. The name was changed for reasons of security.

[ad_2]

Source link